Remembering Tyrone Alumni and World War II Veteran Vincent Hagg

Like the Class of 2020, Tyrone’s Vincent Hagg also missed his senior year at TAHS, but he wasn’t staying home to stop a virus. He was busy fighting the Nazis.

Seventy five years ago today, guns across the European continent fell silent for the first time in over five years. VE (Victory in Europe) Day brought a partial end to one of the most devastating wars in human history. More than 16 million Americans served in World War II, almost 11% of the entire US population.

Hundreds of men from Tyrone were among those who served. Many saw combat and some made the ultimate sacrifice.

Vince would never say that he was there or that he did this or that. You had to bring it out of him, and tell the people what a great soldier and what a great man he was

— Joseph Keirn

One particular Tyrone native, Sgt. Vincent Hagg, served with great distinction in the European Theatre as a member of the Second Ranger Battalion, “D” Company, fighting his way across Europe from the Normandy invasion to the fall of Germany.

Vince Hagg was born July 18, 1925, to parents Ralph and Emma (Schoch) Hagg. He grew up on his family’s dairy farm on land that is now the Tyrone High School soccer, baseball, and softball fields.

Tyrone students and alumni would easily recognize the white house that stands just above the soccer field, but probably do not know anything about the man who grew up there, and what he did for his country.

One man who knew Hagg well is Altoona resident Joseph E. Keirn, a retired Army Command Sergeant Major, World War II memorabilia collector and historian, and a longtime friend of Hagg.

“Vince was a special guy as far as caring for people. He cared a lot about his friends and his family,” said Keirn. “He was never a boisterous guy. When we would tell stories about the Rangers, Vince would never say that he was there or that he did this or that. You had to bring it out of him, and tell the people what a great soldier and what a great man he was.”

Joining the Rangers

Hagg’s war story began during his junior year at Tyrone Area High School. World War II had already been raging for three years and Hagg saw many young men from his hometown volunteer or be drafted.

Walking home from school one day, Hagg and childhood friend Roy Miles made a momentous decision: it was their turn. They went to the local recruiter and volunteered to serve their country in World War II.

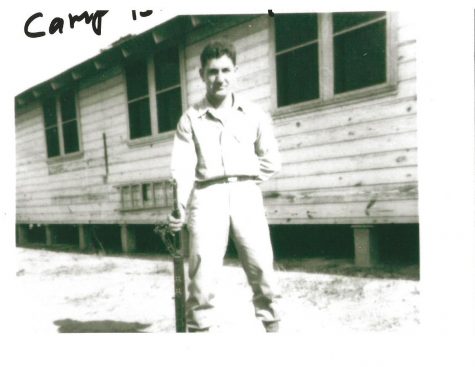

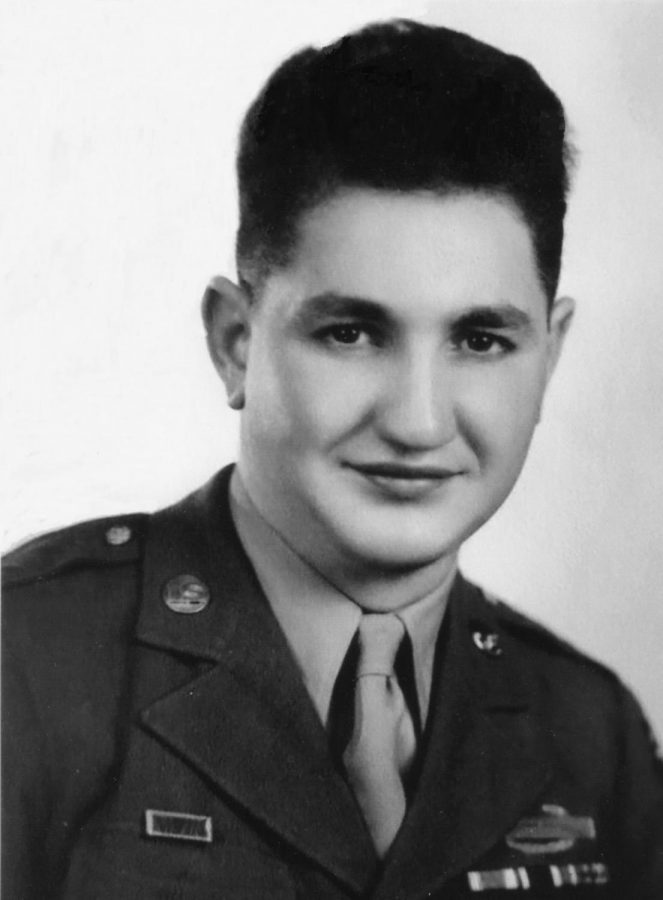

Vince Hagg at Ranger training in Tennessee.

Hagg was soon off to US Army basic training where he impressed his commanders enough to be chosen as one of the youngest members of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, Dog Company.

Formed at Camp Forrest, Tennessee in the spring of 1943, the Rangers were a new US Army special forces unit created in the image of the legendary British Commando units.

The training that the Rangers went through was far more intense than training elsewhere in the military. Each Ranger needed to know how to do the job of every other soldier in the unit. This was needed in case one got killed, the others could continue the mission.

“Geared up in full equipment, including gas masks, the Rangers tromped throughout the Tennessee countryside… [on one occasion Dog Company was ordered] to march thirty-six miles in twelve hours with only one canteen of water each,” wrote historian Patrick O’Donnell in his book Dog Company.

After this period of intense training, in September 1943 Hagg’s battalion was sent to the English coast to prepare for the imminent D-Day invasion.

Dog Company at Pointe Du Hoc

Over the next nine months, Hagg and his fellow Rangers were put through intense training, including extensive rope and ladder climbing courses. They weren’t told what this was for, but in due time they would find out.

“The training [in England] was centered on cliff climbing. I’d had mountain climbing training but nothing like this,” said Ranger Bob Edlin. “The first time I stood on the beach and looked up at those 90 foot high cliffs it just scared the crap out of me.”

Hagg and his fellow soldiers would run the five miles from town to the cliffs, climb the 90-foot cliffs three to five times and run back for lunch. In the afternoon, they would do it all over again.

The Ranger’s objective on D-Day was one of the most audacious and dangerous missions of the war.

Members of the Second Ranger Battalion were given the order to scale the ninety-foot cliffs of Pointe Du Hoc by ropes and ladders, attack the Germans that controlled large artillery batteries at the top, and then disable the artillery guns that were thought to be trained on the beaches below.

“The mission of the Rangers was the most important part of the D-Day invasion. What those Rangers and the rest of the Allied Joint Force did is an accomplishment that remains undiminished by the passage of time,” said Keirn.

While this was the mission he trained for, Hagg himself was not part of the group that made the first assault up the cliffs at Pointe Du Hoc. He was a part of the second wave of allied forces, landing on Omaha Beach on June 7, 1944.

While he didn’t scale the cliffs with members of his company on D-Day, the battle had a major effect on Hagg. Many of Hagg’s friends were part of the force that climbed the cliffs of Pointe Du Hoc, including Altoona natives Jack Kuhn and Sheldon Bare.

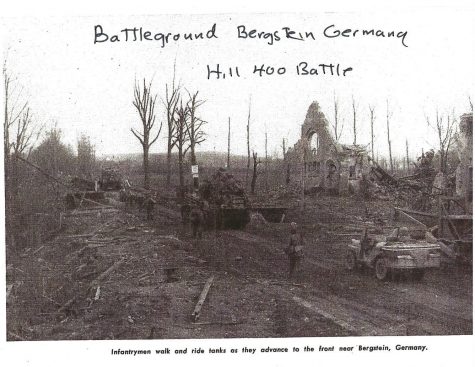

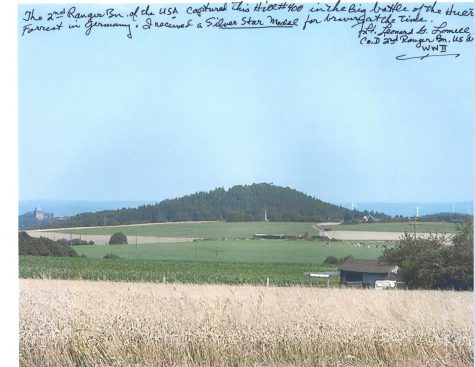

The Battle for Hill 400

Exactly six months after Hagg landed on the beach at Normandy, Hagg would be part of an important but much lesser-known battle to secure a hill critical to the advancement of the American Army across Germany.

The fighting on Hill 400 would be some of the most intense that Hagg and his company would experience during the war.

Hill 400 and the adjacent town of Bergstein, Germany had to be taken to ensure that the German Army would not be able to destroy a series of dams on the Roer River. If destroyed, floods would seriously impede the progress of the American forces into Germany.

Hagg described the scene at Bergstein to O’Donnell for his book on Dog Company.

“It seemed like the Germans knew we were coming. Flares all over the place. The artillery came in like hell. I started down the street. A shell came in. Kenny Harsh was hit. The lieutenant behind me was hit,” said Hagg.

The experience of the battle took a terrible toll on the men. “Those few last minutes before the fight starts are always worse in some respects than the battle itself… Your stomach has that sick, empty feeling, yours, and everyone else’s. You experience a strange sensation of unreality, of sick detachment; you stand aloof from yourself, as it were, and watch yourself struggle with mounting fear,” said Alfred Baer, who served with Hagg in Dog Company.

Hagg and the other Rangers of Fox and Dog Company waited to attack. Their plan was to charge the hill with bayonets. They would have to charge across one hundred yards of open field laced with mines while German machine guns rain fire down on them.

At 7:28 on December 7, 1944, D and F Company charged on Hill 400. O’Donnell describes it this way in his book, “Bud Potratz admitted his mouth turned ‘dry as cotton’ as he charged across the field, firing his weapon at the German lines, and yelling ‘Heigh-ho, Silver!’ at the top of his lungs.”

The charge worked and the Rangers took the hill, but the battle wasn’t over yet. There were many German counter attacks to come.

Bud Potratz, another of Hagg’s comrades at the time, recalls the battle for Hill 400 in an email sent to Joe Keirn.

“The big battle of all battles was on December 7th and 8th, 1944. D Company and F Company had a mission to attack Hill 400 at Bergstein, Germany. Joe [Devoli] was commanding Sargent on December 8th as both companies were decimated…We fought off counter-attack after counter-attack by the [Germans] and finally were relieved at about 11 pm on the 8th,” said Potratz.

While most people think of D-Day as the most intense battle of the campaign, many who were there have said that the battle for Hill 400 was more terrifying.

“December 7, 1944 was the worst day of my life. People say D-Day was the longest day, but I was there, too, and it was much easier on me than Hill 400 in the Hürtgen Forest….It was icy cold, artillery was raining down and we couldn’t even dig in. But we took the 400 meter high hill,” said Lieutenant Len Lomell, 2nd Ranger Battalion, in a 1998 interview.

End of the War

Following the successful battle for Hill 400, the Rangers were again attached to the First Army.

On December 16, 1944, the Battle of the Bulge began, and the Rangers of Dog Company were put on the line with the 78th Infantry Division. While they saw some action in that historic battle, Hill 400 and Bergstein were the last major combat actions for the 2nd Rangers in Europe.

As the war drew to a close Hagg and the men of Dog Company got some amazing sightseeing in.

When the war ended, the guys didn’t make too much of it. We could see it coming.

— Vince Hagg

They came across Schaumburg Castle located in the town of Rinteln, Germany. The castle was owned by the rulers of Schaumburg-Lippe which was a state in Germany until 1946 and it is now in present-day Lower Saxony. They got to tour through the centuries-old castle and found many interesting things, including a large library.

“The library was massive, filled with tomes and maps of all kinds,” remembered Altoona native Sheldon Bare. “I kept rooting through it, and, I couldn’t believe it, I found a book on Altoona!”

Hagg and his fellow Rangers were then sent to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia to serve as corps honor guards.

Then on May 8, 1945, exactly 75 years ago today, Hagg heard the news they had all been waiting for.

Germany officially surrendered. The war in Europe was over.

Their celebration was limited because most of Dog Company expected to be shipped to the Pacific to fight against the Japanese.

“When the war ended, the guys didn’t make too much of it. We could see it coming,” said Hagg.

However, when Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, the 2nd Ranger Battalion learned that they would soon sail home for good.

In mid October the battalion sailed from Le Havre, France to Newport News, Virginia. On October 23, 1945 Hagg’s battalion was officially deactivated. He and his fellow Rangers headed home.

After the War

Hagg returned to Tyrone where he finally received his high school diploma, which was dated 1944, despite the fact that he had actually spent much of that year fighting his way across Europe.

He then attended St. Francis College in Loretto under the GI Bill, graduating with a B.A. Degree in Business Administration in 1950.

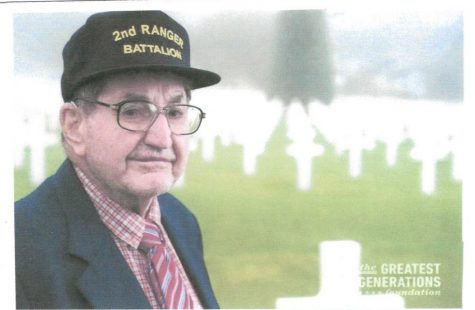

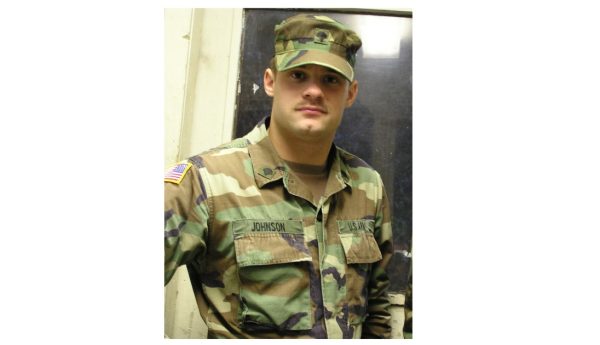

Vince Hagg was able to return to Normandy late in his life with the help of the Greatest Generation Foundation.

Hagg worked for Rockwell International in Pittsburgh from 1951 to 1973 and then moved back home to Tyrone, working for Altoona Pipe and Steel Company as a sales engineer until his retirement in 1994.

Hagg was very active in the community and involved in many organizations in Tyrone.

He was a member of St. Matthew Catholic Church, Tyrone Elks Club, Tyrone American Legion, Anderson-Denny VFW Post, the Bavarian Aid Society, the Tyrone Knights of Columbus, and the Tyrone Monogram Club.

He was also an avid Tyrone sports fan and football booster.

“He went to all of the wrestling matches, all of the football games. I don’t think he missed a football game up until his last year or so,” recalled Hagg’s nephew Joe Hagg.

The Hagg family frequently got together on Sundays. “The uncles would play football against the nieces and nephews… that’s how I remember him. An active person,” said Hagg’s niece, Anne Langenbacher.

Hagg also had many hobbies throughout his life. He enjoyed gardening, cooking, and spending time with his close friends.

He went to all of the wrestling matches, all of the football games. I don’t think he missed a football game up until his last year or so

— Joe Hagg

Hagg also made it a point to attend every Ranger reunion he could, no matter where it was across the country.

In 2011, he was appointed a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor for his action in France.

He and other surviving members of his unit were honored in Washington, D.C. during the 2015 National Memorial Day concert.

Hagg was even able to return to Normandy in 2016 through the generosity of The Greatest Generation Foundation (TGGF), an international organization dedicated to returning soldiers to their former battlegrounds, cemeteries, and memorials at no cost to the veterans.

Hagg lived a long, happy life surrounded by many friends and family.

Vince Hagg passed away on January 3, 2018, at Epworth Manor here in Tyrone. He was 92 years old.

He will always be remembered for his service to his country, and for the great man he was.

“I’m very thankful for veterans like Vince who preserve our freedoms and help protect our way of life,” said nephew Joe Hagg.

Hi! I'm Tyler Beckwith and I am a senior this year at Tyrone Area High School. This is my first year in Eagle Eye and I am very excited to be a part of...

CSM Joseph Keirn retired • May 15, 2020 at 5:04 am

Tyler; Outstanding article and a great job of a great man. I made eight copies of your article and sent them to the families of Vinces Ranger buddies. I am looking forward to working with you at the Keirn WW2 museum.

Chris Nagle • May 8, 2020 at 7:11 am

Excellent article! I throughly enjoyed reading it. Vince and my Dad were first cousins so I knew Vince pretty well but not so much of his war experiencestories. I can hardly wait to share this with my sisters. Thank you.