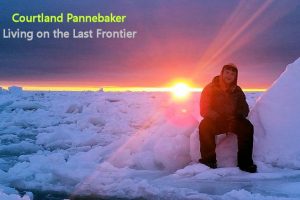

Tyrone Alum Returns to the Alaskan Frontier

With only four hours of daylight and an average daily temperature of less than 18 degrees in the winter, most people are not cut out for life on the frozen tundra of Gambell, Alaska.

But 2012 Tyrone High School graduate Courtland Pannebaker is not “most people.”

Three years ago, Pannebaker embarked on an adventure of a lifetime when he accepted a teaching position in the tiny town of 681 people on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea.

“I think we have gone through seven or eight different teachers throughout the grades in my three years so far and we only have 15 teachers. We have even had several principals,” said Pannebaker.

Defying the odds, this fall Pannebaker returned for his third year teaching preschool at Gambell’s only school. Despite the difficult environment, Pannebaker is truly enjoying his time in Alaska.

Growing up in central Pennsylvania, Pannebaker has always loved the outdoors and spends much of his free time in Gambell hunting, fishing, riding four-wheelers and snowmobiles.

“In the morning, I warm up my four-wheeler and brush off the snow. I then commute to the Head Start in the middle of the village. I teach, complete my coaching, and then look to go exploring. You can ride on the beach, climb the mountain, or go for a ride in the tundra,” said Pannebaker.

He also enjoys spending time learning about the culture of the native Siberian Yupik people. He enjoys going to his friends’ houses to learn how to prepare native foods. Pannebaker has learned Yupik dance, and he’s even learning the traditional art of carving of walrus tusk and whalebone.

The Yupik people have special permission to hunt whale and walrus as part of maintaining their traditional subsistence culture. Part of Yupik tradition is to use every part of the animal; nothing is left to waste. The meat is frozen and dried to sustain the village throughout the year, the hides are used to cover and protect boats, and the tusks and bones are carved into intricate pieces of art. Not only does whale and walrus hunting sustain the people, but it provides them with a vital source of employment.

Back at home, Courtland’s mom, LeeAnn, misses her son but is proud of what he has accomplished and learned in Alaska.

According to LeeAnn, teaching and living on a remote Alaskan island can be harder for a non-native than they might expect. It is difficult to adjust to days of continuous darkness or daylight. It can be hard to live without the things Americans are used to having like TV, a car, a store on the corner, and in some places even running water or plumbing.

“I think [Courtland] stays because he enjoys learning about the culture and ways of the village,” said LeAnn Pannebaker, “He has made so many friends and many families invite him into their homes for family events and dinners. Courtland isn’t afraid to go out and meet the people of the village and also participates in their events to try and learn about their culture and meet more people.”

While Pannebaker loves the outdoors, more than anything, it’s been the people that have kept him there.

“Courtland has completely acquired native status in my opinion,” said one of Pannebaker’s Yupik friends, Lucas Aningayou. “He has impacted not only my life, but also the lives of the village of Gambell. He participates in school events, helps anyone in need, and has earned the respect of the community elders.”

Because of the cultural differences between them and their students, many teachers in remote places like Gambell have a hard time conveying the importance of education to their native students.

Pannebaker, however, has not had issues with his students.

“For me, it’s easy. I teach preschool. The students seem to come motivated and excited every day due to their age. I also try to connect with them on a personal level. We have a really good and trusting relationship. Students will try harder and want to make you happy if they feel you care about them. Along with the personal relationships, I find that if you keep the activities short and make the transitions fun, that the students can remain very engaged,” said Pannebaker.

While Pannebaker has not had any issues engaging his students in learning, he has had difficulty with communication. The biggest barrier between him and his students when he first arrived was language.

“It is a guttural language and some of the letters make different sounds than in English. But after hearing it and practicing it for almost three years now, I am beginning to get better. Sometimes a student will say a Yupik word that I don’t understand, but my aid, Apaay, is there to help. She grew up on the island,” said Pannebaker.

Pannebaker initially had trouble relating to his students because he had such a different upbringing from them. He had a hard time understanding their values and beliefs because he grew up in a completely different society.

“As I went out and had experiences, it got much easier to connect because I had a better understanding of who the people really are and what their values are. One family even considered me their ‘white son’,” said Pannebaker.

Pannebaker has made many good friends who have helped him adapt and learn more about the Yupik culture.

“I have taught him how to fluently speak Yupik, as well as names of the village, Eskimo dancing, and guided him across the entire North of the island. I try to teach him the island’s history and how to survive here. My family lets Courtland try all kinds of native food when we have it and he is always happy to eat with us and have the opportunity to try the food,” said Aningayou.

Pannebaker has made an effort to immerse himself in the culture of the island, from the food to the native dances.

“I really enjoy watching and doing the dances, and I have learned a few dances just by watching on Wednesdays at the school. We get out an hour early on Wednesdays and all of the students and community come to dance. Every dance tells a story and some families/clans even have their own songs and dances. The Yupik people had no way of writing or recording their history and knowledge, so dancing was a way to pass on traditions, clan history, and stories,” said Pannebaker.

He also likes to lend a hand when the village catches a whale or has a big project. Since the village is so small, everyone is needed to step up during the hunt.

“Being from such a small village there aren’t as many people trained or even people period to perform tasks. I have found myself doing many things spur the moment just because they needed to be done and there is nobody else to do it. That’s one of the biggest differences from the lower 48. There is nobody else around to fix your problems. We have our village and ourselves and that’s about it out here,” said Pannebaker.

Lending a hand is not a new concept for Pannebaker. According to his mom, Courtland has always been willing to help those in need.

“I think being a boy scout helped a lot with that trait as it taught him to step up and always be helpful. I also think his participation in sports teams, while a student at Tyrone, empowered him to do things he might not normally do. His willingness to help is one of the reasons, I believe, he has been successful there. He isn’t afraid to jump in and help pull the whale from the water or he will offer an elder a ride on his 4-wheeler so they don’t have to walk,” said LeeAnn Pannebaker.

Pannebaker has also stepped in the last three years to coach cross country running in the fall and cross country skiing in the winter.

“Our team had no coach, but students wanted to ski, so I stepped up and decided I was going to learn. I have had tremendous support from some other great coaches and the students are happy to teach me their tricks and tips as well,” said Pannebaker.

Hi, my name is Emma Hoover, and I am a Senior at TAHS. This summer I was a Lifeguard at Delgrosso's Amusement Park. During the school year, I’m a...

Kent Lauridsen • Apr 17, 2020 at 7:24 pm

Emma, I second Dr. Cramer’s comments. You have a bright future. Kent

Dr. Anne Mong Cramer • Oct 19, 2018 at 8:37 am

Courtland is a graduate of our Elementary Early Childhood Education program at Penn State Altoona, and we are so proud of him.

Emma Hoover, you are a very talented journalist, and based on you bio, an all around remarkable person. Keep up the good work. Penn State will be proud to have you.