History is being rewritten by science at the historic Fort Roberdeau in Sinking Valley.

Using high-tech geological tools, a team of scientists, archeologists, students, and volunteers led by Juniata College Professors Ryan Mathur and Jonathan Burns have discovered the original location of the Revolutionary War-era fort and unearthed some interesting artifacts.

Their findings were published in December 2023 in the journal Historical Archaeology.

“Dr. Burns and I were able to put geology and archaeology together to help tell the story of what was going on here in the late 1700s,” Mathur said.

The project has brought together a diverse group of experts to use technology to conduct historical research.

“We had two chemists from the University of Florida and Rutgers University help out, the drone person was a hydrogeologist from Westchester. We had a geophysicist who was also a Juniata grad help out, and several historians from the fort,” Mathur said. “So it was a very diverse team. One of the most diverse teams I’ve ever worked on, and that’s why the product is kind of unique.”

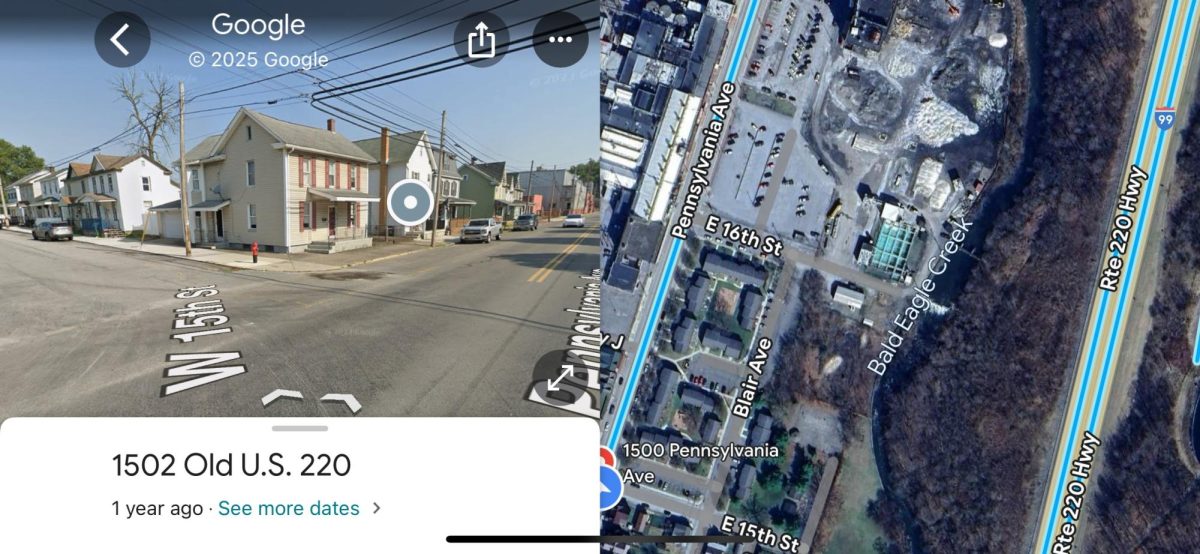

The fort, located within the Tyrone Area School District in Sinking Valley, was originally built during the American Revolution by Daniel Roberdeau under orders from General George Washington. Its purpose was to protect lead mining activities from Native Americans and British sympathizers.

Lead for musket balls was vital to the American war effort. A British naval blockade prevented the Continental Army from receiving ammunition from Europe, so when Washington learned there were lead deposits in Sinking Valley, he authorized the fort’s construction to provide the army with lead for musket balls.

When the naval blockade was broken and the Americans began to receive lead from the French, the fort was abandoned. But the legend of the Revolutionary War-era frontier outpost persisted, and the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

A reconstruction based on historical documents was built in 1975, but the location of the original fort and mine were lost to history.

That is until 2015, when Mathur, a geochemist and the chair of the geology department at Juniata, saw an opportunity to use technology to solve the two most-asked questions by visitors: “Where exactly was the original fort?” and “Where was the lead mine?”

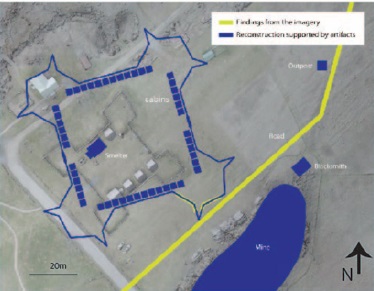

Mathur and his students used light-detection and ranging (LiDAR) and thermal imagery from drones, geological mapping, geophysical electrical resistivity surveys, metal detecting, and lead-isotopic analyses of artifacts to find the original foundation of the fort, areas that were mined for lead, and other structures within the fort.

“In geophysics, you can use different techniques to see in the subsurface. So we ran a bunch of experiments over areas we thought the mine might be. In 2017 we identified a pit that was historically accurate with the record by using the resistivity geophysical technique. So we actually identified where the mine was in the middle of a current cornfield,” Mathur said.

The team also used drones to find the original footprint of the fort.

“Using LiDAR and thermal imaging we can see very subtle variations in the elevation and plant life, we were able to find the corner of the the fort, the Bastion, and we also found a road that led to the fort,” Mathur said, “That allowed us to draw a map of what the original fort looked like.”

It turns out that the original fort lies on the same land as the reconstructed one. The original structure was similar in shape to the reconstruction, but almost two-thirds larger than what is on the site now.

“We found an area that we thought was a blacksmith area, we found tools that we thought were associated with the mining area. So that’s where we thought the mine was,” said Burns.

Local resident Scott Padamonsky, an employee of Tetra Tech, an environmental consulting firm, has been volunteering on the project for many years and is excited by what they have found.

“It’s interesting because I grew up in this area. I remember coming here as a youth. We were told that they didn’t even think the fort was here. So throughout the process of being out here and seeing the proof that the fort was here, and in fact, it’s much bigger than what they even thought it was, is a pretty interesting thing,” Padamonsky said.

The team is currently investigating an area that they suspect is the location of the original lead mine. The area was overgrown but they had trees and brush removed and have begun using metal detectors to search the area for artifacts.

Mathur said that the type of mining that occurred at Fort Roberdeau was nothing like the deep shaft coal mining typically associated with central Pennsylvania.

“We really didn’t do that type of mining in the United States until much later,” Mathur said. The Fort Roberdeau mine was a surface mine, probably no deeper than 30 feet.

In April, Eagle Eye members Lexi Hess, Kenzie Soellner, Tony Hughes, Jake Rice, Rocky Romani, Eli Walk, Alex Shock, Aiden Betke, and Eagle Eye adviser Todd Cammarata visited the site to report on and participate in the project at the same time.

The students were given hand-held metal detectors called pointers to locate any metal within the dirt along with small shovels to dig up the ground.

Dr. Burns and his team went around with a larger metal detector and flagged areas of interest for the students to dig.

The students recovered several artifacts including a musket ball, another possible musket ball or piece of scrap lead, a possible wagon part, a chain link, and a couple of early nails.

“I really enjoyed getting the opportunity to get out and find historical artifacts. I found it to be a very interesting topic,” said Eagle Eye student Kenzie Soellner.

The musket ball and lead were considered to be particularly significant, so the exact location where they were found was mapped using a highly accurate GPS.

“Anytime you find an artifact that’s as significant as a piece of lead, especially on a site like this, we use a really highly accurate GPS. That can then be dumped into a mapping program or GIS so we can continuously keep track of all the finds. A decade or two decades could pass and we would be able to build up this library of finds,” Burns said.

The students’ finds could be on display at Fort Roberdeau for their historical significance.

“It’s pretty fun finding little pieces of history. I think it’s interesting. That might make me a nerd, but that’s okay,” Eagle Eye student Jake Rice said.