My name's Carly Crofcheck. I've been in the Tyrone Eagle Eye for four years and I'm a Senior at TAHS. Last year I was the Editor in Chief, this year...

May 3, 2016

Showing a handful of grim gray photographs of the Holocaust, 91 year old Dr. Eva Olsson told her horrific story of survival to students from Mrs. Burket’s and Mrs. Deskevich’s honors and dual enrollment classes along with YAN members who attended the event at the Penn Highlands Community College in Johnstown on April 5, 2016.

Olsson was one of the fortunate survivors who walked away from one of the most horrific genocides in human history, an injustice masterminded by Adolf Hitler and executed by the Nazi regime.

For more than an hour Olsson told her story in gripping detail. As the horror she endured was revealed, she spoke of the evils of hatred, bullying and intolerance. Her words touched the hearts of those who listened.

With a theme of bullying, she used her story of the Holocaust and its extreme examples of hate.

“I was 19 when I was bullied by the Nazi’s. Why? Because I had the wrong hair color? Maybe because I was Jewish? It doesn’t matter if you’re Asian, black, Indian, that should have no effect on anyone, the only thing that effects people is attitude. Not color or Culture, that attitude can determine your success. Being successful as a human being starts with how you treat each other.”

After 50 years of looking for answers and searching for peace, Olsson broke her silence about the atrocities she and her family suffered during the holocaust, and now tells her story to millions around the world.

Olsson is now an author and public speaker telling the story from the inside of concentration camps with frankness and detail.

“I thought she was an amazing individual with a powerful story we should not allow ourselves to forget,” said YAN advisor Tracy Redinger, “This may be the last time any of us have the experience of hearing testimony from a survivor of the Holocaust, and I think we have a moral obligation to ourselves and future generations to share these experiences and what we’ve learned so that we can be part of the solution and not the problem.”

Her presentations have moved some to tears. At times, emotion even welled up in Olsson’s eyes as she remembered the horror of the Holocaust.

“I made a commitment not to allow my pain to control my life,” said Olsson.

According to Olsson it is because of Hitler that she controls her pain. She will not allow the perpetrator to control her any longer. That’s why she chooses to speak against it.

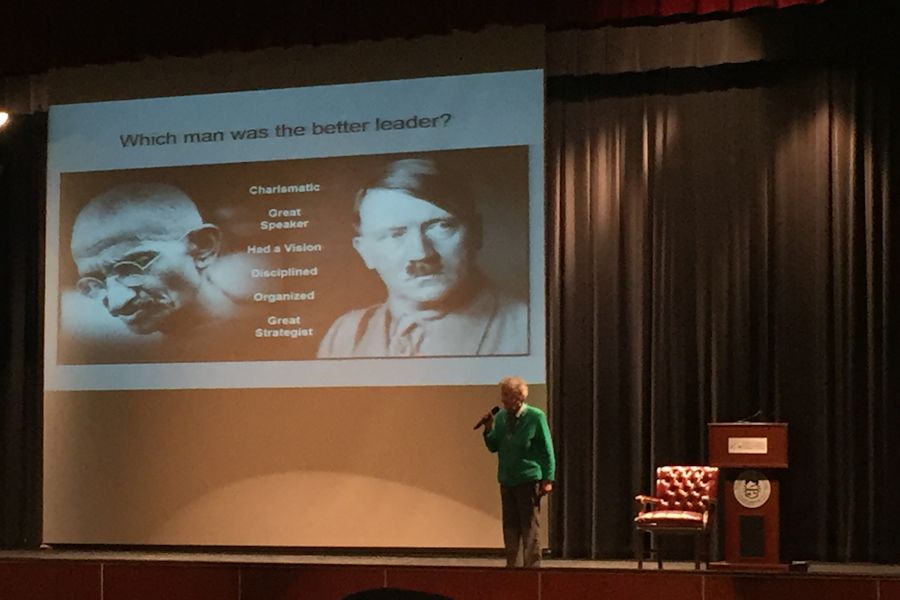

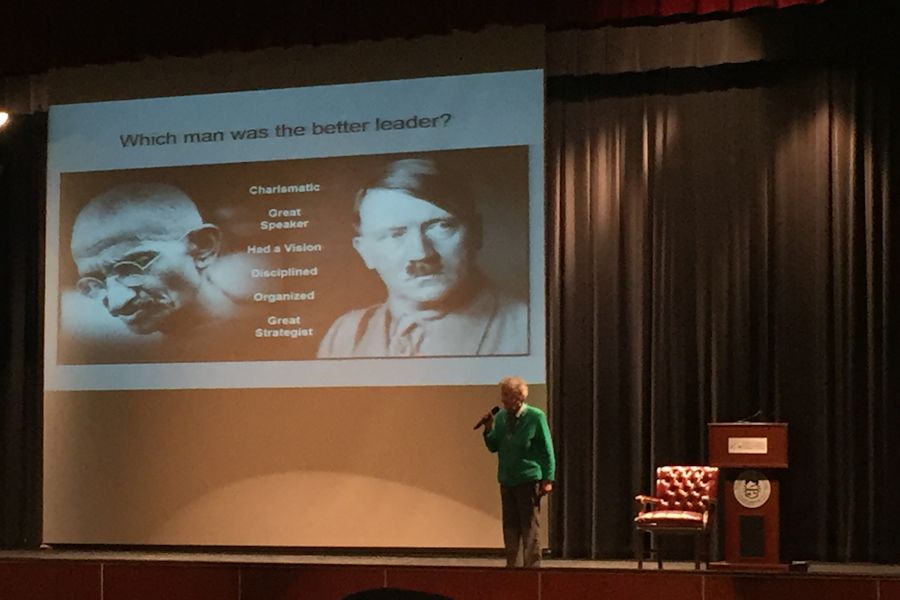

Olsson compared leadership traits of Hitler and Ghandi. Both with similar skills, but used those skills in opposite ways. Ghandi led people to light, Hitler led his people to darkness.

Olsson was born Ester Malek in eastern Hungary in 1924. In March 1944, Germany occupied Hungary, where Olsson and her family were living. She came from a orthodox Jewish family of six children.

“In May 1944, a man came in the square with a drum,” said Ollson, “He wanted everybody go outside and hear what he had to read from a piece of paper. We were ordered to pack our bags and we were told we have two hours and that we have to march to the railway station that was seven kilometres away from where the ghetto was.

“They told us they’re taking us to Germany to work in a brick factory. The sign said Auschwitz,” aid Olsson.

When the cars opened from the outside, many of the people locked inside let out a sigh of relief that now they were going to have fresh air and water.

“Except for us, there was no water and the air was nauseating,” said Olsson. “We couldn’t relate it to anything. There was smoke coming out of the chimney, high towers, machine guns. I turned to my mum and I said, ‘This doesn’t look like a brick factory.’ No, Auschwitz was not a brick factory, it was a killing factory. The smell that we smelled was the smell of human flesh burning.”

Everyone that was sent to the factory was sent through a selection process. The guards wouldn’t speak, they only pointed left and right. Olsson was sent to the right, her family to the left. She didn’t know where her family was going to be sent. When she turned to look for her mom, it was too late.

“When I didn’t see her I wished I could give her a hug and tell her how much I love her.”

The women and children on the left were forced into gas chambers.

“After 20 minutes it was silent. The poison came out of the shower heads. Children died 1st, their heads were crushed because other bodies fell on them. Some that were still breathing after 20 minutes were shot, and after that the dead women were pulled out of the gas chamber and their heads were cut off, human hair was shipped to Germany to manufacture socks for U-boat soldiers,” Olsson said.

Six million Jews and five million non-Jews including gypsies, political activists, priests and nuns were killed. Burned, gassed or starved to death.

“Among the 11 million were 1.5 million children who were brutally and systematically annihilated by those Nazi bullies,” said Olsson.

Gypsy children were used as medical experiments, including sewn together twins back to back to see how long they could survive, injecting them with tuberculosis and other diseases and exposing them to radiation and high voltage.

“They made sure that the male would never father a child, and the female would never bear one,” said Olsson.

The Nazis stripped her of absolutely everything, except for her will to survive.

“The only thing the Nazi’s couldn’t strip you of is the strength of one’s spirit.”

For two years, men were sent to work in labor fields and only 150 bowls of “surprise soup” were given out to 200 men. The soup contained human bones, hair, old potato skins, and dirty water.

Beneath the story of her Holocaust experience is a strong message that bullying, racial slurs and “standing by and doing nothing should not be tolerated.”

“At one high school, when I showed a picture of the concentration camp, one student started crying. Afterwards, the school chaplain called me into the office and that student told me he didn’t want to be a Nazi any more. His father was a well-known neo-Nazi. Am I making a difference? I hope so. I hope I’m making a difference.”

“We have to teach our children not to judge because of religion, origin, skin color and the shape of your eyes. When kids are unhappy and angry, they take it out on other children.”

Olsson advocates for an end to bullying.

“Taking no action against bullying is regressive, just like the way things were in Europe. I’ve made it my mission to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves,” she said, referring to those who died,” said Olsson.

Olsson and other women worked on the factory grounds of the Krupp Ammunition Factory as laborers.

The women were showered and their hair was shaved off. They were issued long gray dresses, wooden shoes and one gray blanket. Food was rationed, a normal day’s ration included a slice of dark bread made mainly from sawdust and a cup of watery soup.

Allied forces bombed the factory while they were in the fields. Because of this the women were forced to sleep in a large hole in the ground through the winter. Straw was inside to sleep on, which was rotten because it was also used as a toilet.

They were eventually forced to march to another city.

“We were being moved because the soldiers didn’t want us to be freed,” said Olsson.

On April 15, 1945 at 11 a.m. Olsson along with her prison mates were liberated by British and Canadian soldiers.

Her pursuit of peace, tolerance and equality was born from the horrors of her past.

“Next time you have the urge to say to someone ‘I hate you’ think of a person your age who died because they were hated,” said Olsson.

After the war Olsson moved to Sweden, where she had the opportunity to see what humanity is all about.

“The Swedish didn’t care about your origin or skin color,” said Olsson, “they showed us respect with compassion and tolerance. This is what we must teach our children.”

“I can’t change the past but I’m asking you to help me. Teach your kids to be caring human beings, not to be judgmental, resort to name calling and bullying. There’s no good side to this, no win-win, just lose-lose. But, the most important thing you can teach your children is not to be bystanders, but to be somebody who can make a difference and show we care,” said Olsson.

Eleven million voices were silenced by hate.

My name's Carly Crofcheck. I've been in the Tyrone Eagle Eye for four years and I'm a Senior at TAHS. Last year I was the Editor in Chief, this year...