Hey! My name is Kathleen Cempa and I attend the Grier School for girls as a sophomore! I’ve spent my entire life here in Tyrone and attended school at...

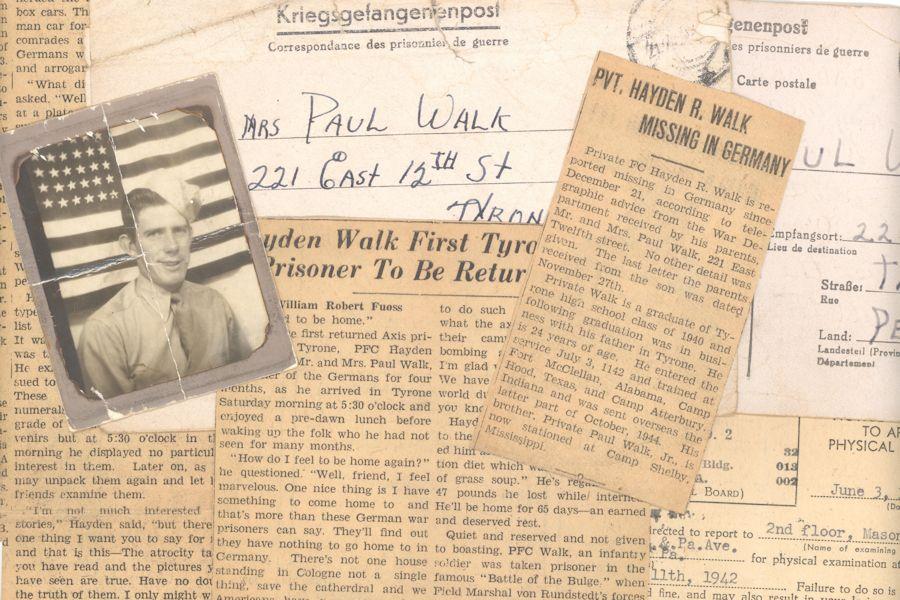

TAHS graduate PFC Hayden Walk of Tyrone was liberated from a notorious German POW camp 70 years ago today, April 2, 1945.

April 2, 2015

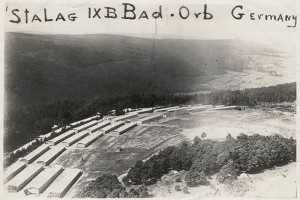

Seventy years ago today Stalag IX B, one of the most notorious Nazi POW camps of World War II, was liberated by Allied Forces.

Among the approximately 3,400 US prisoners of war freed that day was Tyrone native Hayden Walk. Walk was a prisoner at the camp for four months after his capture in December 1944. When the camp was liberated Walk became the first POW from the Tyrone area to return home after the war.

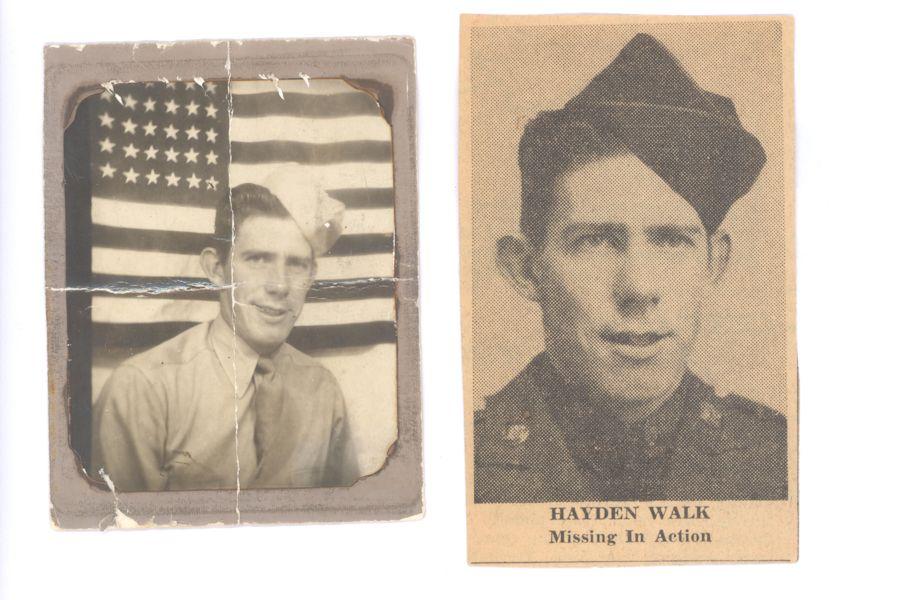

Hayden R. Walk was born and raised in Tyrone and graduated from Tyrone High School in 1940. Until the war interrupted his life, Walk worked with his father as a painting contractor in Tyrone. Like millions of other young men of his generation, he received word that he had been drafted into the United States Army. He was 21 years old at the time.

Walk departed from the Tyrone train station for basic training on July 3rd, 1942. He spent time training at Fort Benning, Fort McCellan, Camp Hood and Camp Atterbury. When his training was complete he was sent to the European theater sometime in October 1944. Not long after that he was sent into battle.

Walk soon found himself on the front lines in the Battle of the Bulge which lasted from December 16, 1944 to January 25, 1945. In the early days of the battle, Walk’s company commander called Walk and his comrades together and told them they were surrounded and could not keep fighting. After a couple of hours spent burying mementos, pictures of loved ones and anything of value that the enemies could take from them, Walk and his company put up the white flag. They were taken prisoners of war on December 19th, 1944.

Back at home, his family was starved for information.

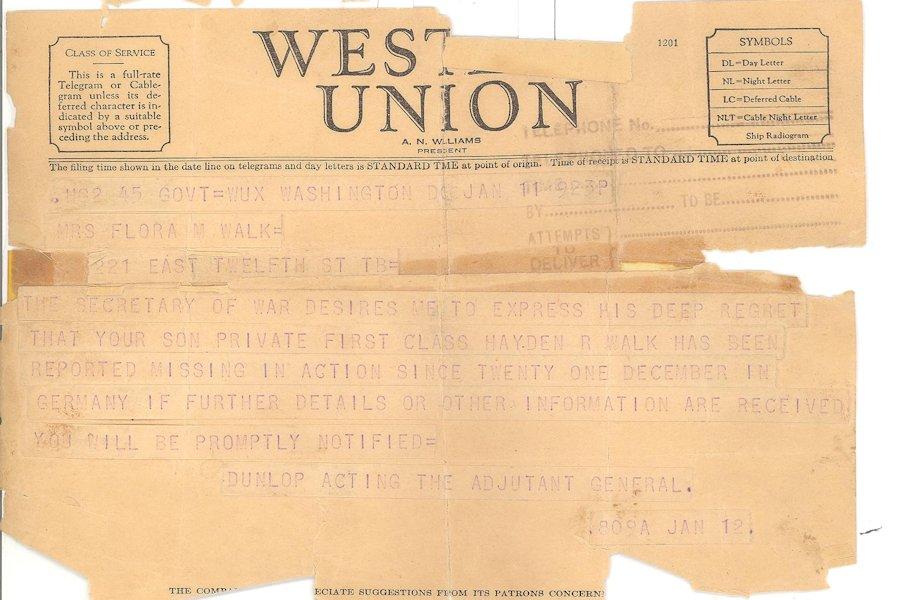

Often during the war, a taxi would come to houses to deliver letters from the Western Union. No family wanted to have the taxi stop at their house, because those letters usually informed families that their son, brother or husband was missing-in-action or killed. Women would sit on their porches or look out their windows praying that it wouldn’t stop at their house.

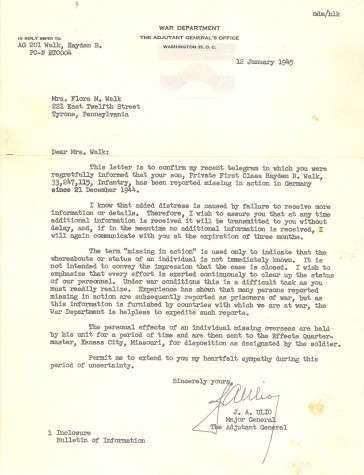

Unfortunately, on January 12, 1945 a taxi stopped in front of the Walk family home at 221 East 12th Street in Tyrone. The telegram given to Mrs. Walk simply said that their son was missing-in-action, leaving the family in anguish, wondering if their son had been killed or captured.

Unknown to his parents at the time, their son was alive but in a very dire situation. He and his fellow prisoners were being marched 35 to 40 miles a day for three days through the German countryside.

It was very brutal winter that year, even though it was still only December. On the three day march Walk and his fellow soldiers received no food or water and many had inadequate shoes and clothing. Soldiers who were fast enough scooped up some snow to drink, but only if the Germans weren’t watching. According to Walk, the Germans were nasty and arrogant. German civilians would throw rotten eggs and tomatoes at them, yelling and calling them names.

When they finally reached a train station they were forced into box cars. From there things only got worse. They were herded into the boxcars like cattle with no room to move. Walk recalled men crying. They were locked in the boxcars for about a week, stopping only once for water, which was put into helmets that were also used to go to the bathroom in.

After their horrific train ride, Walk and the other soldiers arrived at one of Germany’s worst prisoner of war camps, according to the State Department.

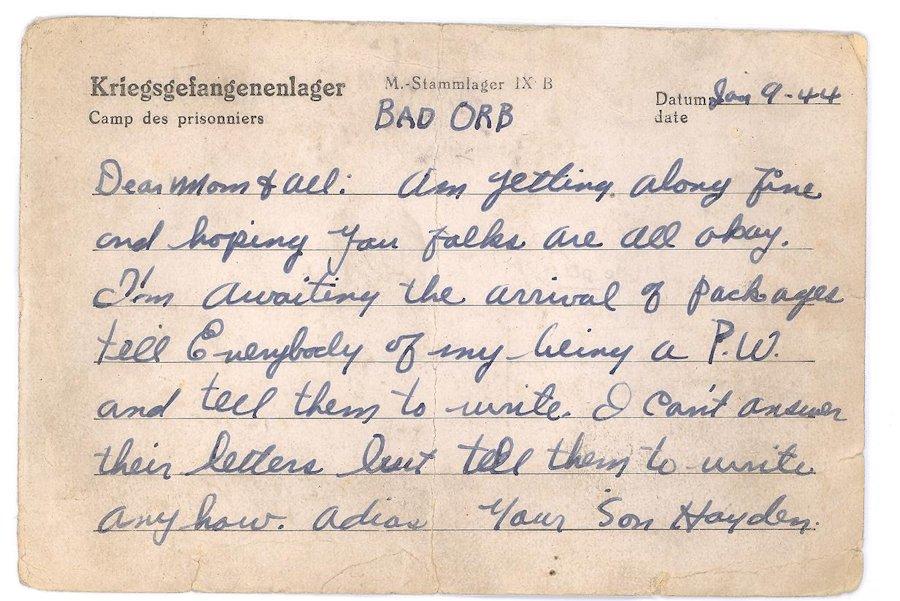

Stalag IX B was located in Bad Orb, Germany and held Serbian, Italian, French, and Russian P.O.W.s in late December of 1944, when 985 American soldiers, including Walk, captured during the first two days of the Battle of the Bulge were sent there.

Walk’s family received word of where he was being held captive on March 1st, 1945.

“Report just received through the International Red Cross states that your son, Private First Class Hayden R. Walk is a prisoner of war of the German government,” is the only information that the letter provided.

By the end of the war, the town’s name,”Bad Orb”, held a deeper meaning to US servicemen. In total the camp held around 4,700 American POWs, far more than it was ever equipped to handle. The food there was terrible and was rationed into insufficient amounts.

“Toward the end we were lucky to get a slice of very poor bread and for days and days, even weeks, we were ‘favored’ with grass soup, possibly you’ve never tasted grass soup! Well, I hope you never will be compelled to live on it,” noted Walk in an interview with the Daily Herald immediately after his return home.

Over the course of his captivity, Walk lost approximately 40-50 pounds.

Rations in the camp consisted of 300 grams of bread, 550 grams of potatoes, 30 grams of horse meat, one-half liter of tea and one-half liter of soup, made from grass and putrid greens that was watered down.

However, near the end of the war the ration was cut even further, and POWs were only receiving 210 grams of bread and 290 grams of potatoes per day. Only one delivery of Red Cross food parcels ever reached camp, enough though in many POW’s letters home, including Walk’s, they were told to specifically ask for them.

In one letter written by Walk he said, “Dear Mom, I am well and hope this letter finds all of you the same. I don’t want you to worry too much about me, as I’ll get along okay. When you get the Red Cross Card send me all the packages you can. Tell everybody I said hello. -Hayden”

Even though Walk’s Mother sent several packages, he and fellow soldiers never saw them, because the Germans would confiscate them.

Conditions in the camp were deplorable. 290 to 500 POWs were crowded into one-story barracks with made of either wood or tar paper. The barracks were divided two sections with a “washroom” in the middle. These washrooms were often just holes in the ground and a cold water tap, where prisoners could try to clean their hands. Each half of the barracks had a single stove with a ration of wood that would provide heat for only about an hour a day during the winter. Bunks, if the barracks had any, were triple-deckers put in groups of four. Several barracks had no bunks at all, leaving around 1,500 men sleeping on the floor. POWs who were lucky received one blanket, but when the camp was liberated some men had no blankets at all. All the barracks were in some state of disrepair, with broken windows, leaky roofs and substandard lighting.

During his internment, Walk worked in the kitchen. According to a story that he told his daughter Connie, once he was accused of taking food, even though he swore he hadn’t. In almost any POW camp, if you were caught stealing food you were shot right away and the rule was even more strictly in enforced in Stalag IX B. A furious SS officer forced Walk to his knees, pointed a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. However, the gun jammed and his life was miraculously spared.

Near the end of the war men were dying frequently in the camp from diseases, abuse and starvation. One thing Walk was extremely ashamed of was how he and the other prisoners would treat the dead. When he and his fellow prisoners saw someone dying, they would wait until he took his last breath and immediately took whatever he had on him. Food, clothing and boots, if he had boots, were all immediately taken by other prisoners. Things like shirts, pants, blankets or boots were extremely valuable considering that many only had dirty rags to wrap around their feet. Men would do anything they could for them, even if it meant stealing from their dead comrades.

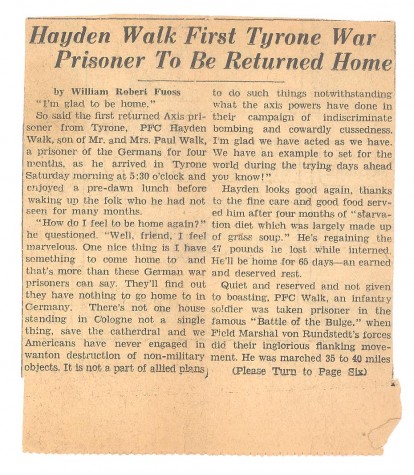

Walk was liberated from the Stalag on April 2nd, 1945. In a strange coincidence, one of the American soldiers that Walk met that day happened to be a fellow Tyrone citizen, Sam Forte. Forte owned a shoe repair shop in Tyrone on 10th street, next to the Gardner’s Candy Store. When Forte walked into the camp Walk did a double take and thought he was dead or dreaming when he saw someone from home staring back at him.

Like many of the other prisoner’s, Walk was far too weak to stand, let alone greet his liberators. Doctors examined him and determined that he was days away from dying. After his brutal stay at Stalag IX B, Walk had to be carried out of the camp and was sent to a hospital in France to begin his recovery.

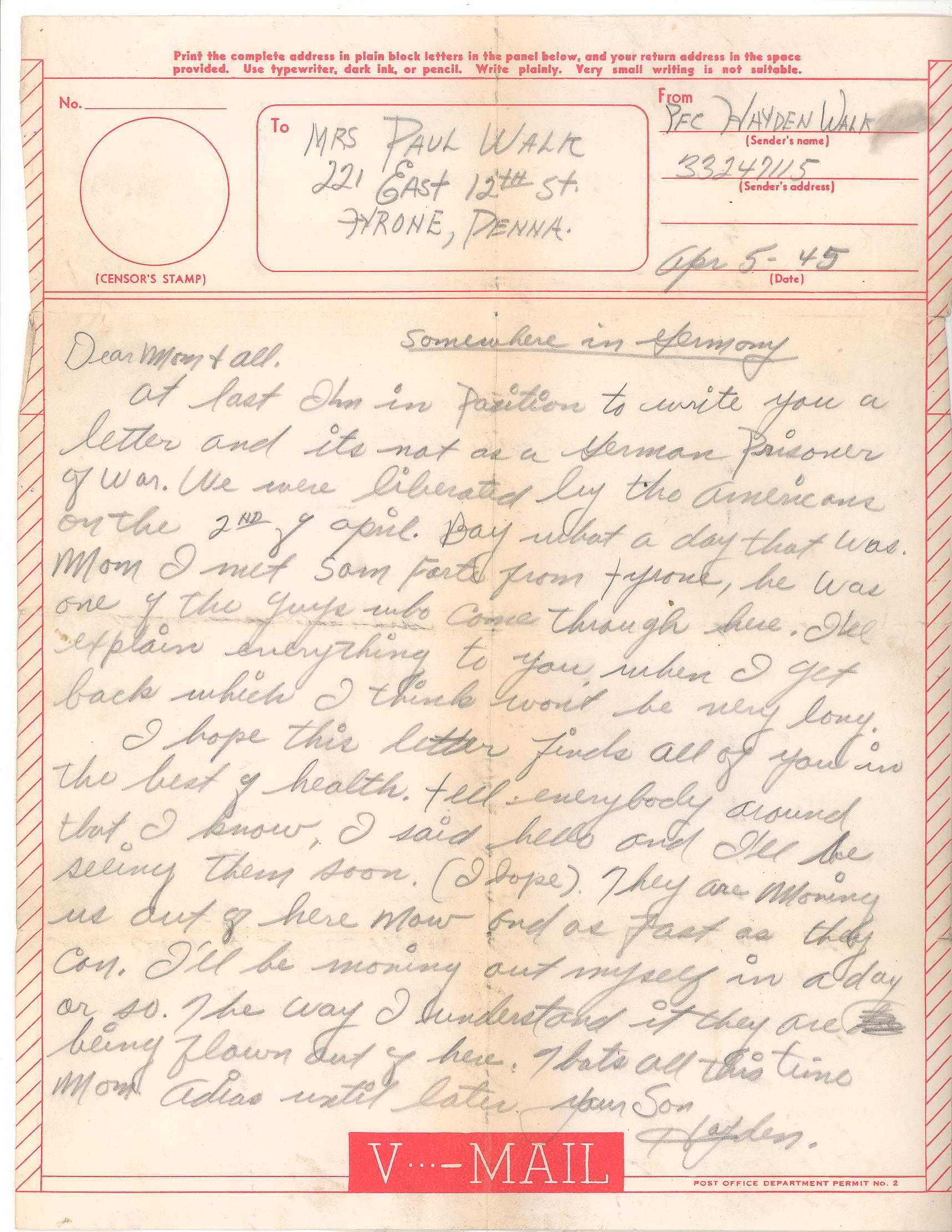

On April 5, Walk was able to write his first letter home as a free man. He began the letter “Dear Mom and all, at last I’m in a position to write you a letter and its not as a German prisoner of war. We were liberated by the Americans on the 2nd of April. Boy what a day that was.”

Walk’s next letter home was written from a hospital in France on April 16, 1945. In it he said “I’m felling pretty good now but I was in pretty sorry condition for awhile. Life as a [prisoner] in German was pretty rough but I won’t go into detail about that now.”

In an interview with the Tyrone Herald soon after his return, Walk spoke frankly of both the joy of being home and the horrors of war that he witnessed in Germany.

“How do I feel to be home again? Well friend, I feel marvelous,” said Walk.

“The [atrocious] tales you have read and the pictures you have seen are true. Have no doubt the truth of them. I only might wish I was permitted to tell you of them, but for the present I shall merely add that the worst has not been told. The Germans are just as they have been portrayed to you over the air and in the press. The atrocities are correct in every respect,” Walk told the Herald in 1945.

Walk did not speak to his children about his war experiences until they were teenagers, and even then he glossed over most of the details. It wasn’t until he reached his late 70’s and early 80’s and his children were grown that he began to talk about his experiences in depth and finally answer questions.

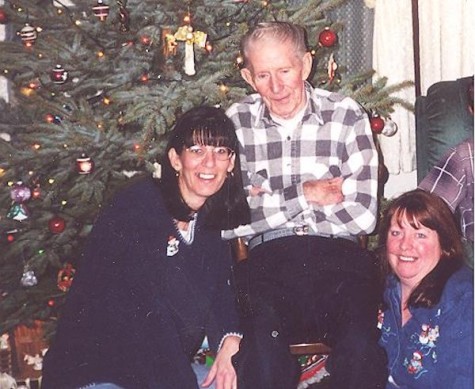

Walk’s daughter’s Connie Shaffer and Denise Crispell still live in Tyrone. His son Mike, a Vietnam veteran, lives in Ephrata, Pennsylvania.

According to his daughter Connie, like many veterans of the POW camps Walk developed a drinking problem after his return home. She also recalled that whenever her father would hear the song Danny Boy he would shut off the radio or TV because it would remind him of an Irish member of his company who would often sing that song. The sound of it would take him back to the unpleasant memories of war. Walk also suffered from chronic diarrhea, which he blamed on his malnutrition, until the end of his life.

Walk died at age 84 on August 1, 2005. His story, unique in it’s own ways, but similar to many other soldiers who endured harsh internment after being captured on the battlefield. Many never saw their families again. It is extremely important to remember their sacrifices and what they went through, as they have paved the way for all of the freedoms we often take for granted.

Hey! My name is Kathleen Cempa and I attend the Grier School for girls as a sophomore! I’ve spent my entire life here in Tyrone and attended school at...

Logan Dasher • Feb 22, 2024 at 11:37 am

Thank bud

Christopher Davis • Mar 2, 2020 at 1:57 pm

thank you for writing about my step sister Hayden

Julie Walk • Dec 17, 2019 at 5:02 pm

Thank you for the wonderful article. Hayden was my husband’s uncle. Our son, Nathan Walk, is a senior at Tyrone High School this year and this is a proud part of his heritage. All the memorabilia here are awesome finds!

Scott Hiller • Apr 2, 2015 at 1:55 pm

I knew Mr. Walk, that he was a former POW, and that he had suffered. The article shed some light on how much he suffered and was well written. Mr. Walk was one of several former POW’s from Tyrone. As far as I know, the only former POW we have still living in Tyrone, is Primo Lusardi, age 94. The trials of the Euopean Theatre POW’s is not as well known, as is the horrible treatment meted out to the Pacific POW’s by the Japanese Empire. I was glad to see Mr. Walk recognized for his service. If one is interested, a good book to read is “The Last Escape: The Untold Story of Allied Prisoners of War in Europe 1944-45”, by John Nichol. Rest in Peace Mr. Walk!

Connie Shaffer • Apr 2, 2015 at 10:07 am

As my sister and daughter said this is a wonderful tribute to our dad (grandfather). Kathleen, you have an amazing talent for writing! And it is so important to not forget the sacrifices that have been made for all of us to have our freedom – then and now.

Kathleen Cempa • Apr 2, 2015 at 9:29 am

Your welcome! It was truly my pleasure to write this story and I am glad it moved you! Hayden and his story carry an important message that I hope everyone who reads this story receives!

Stacy Shaffer • Apr 2, 2015 at 8:55 am

Thank you so much for writing this article about my pappy Hayden! It is an amazing tribute to him and a great reminder to be thankful to all those risked or gave their lives so that we can be free. Thanks again!

Denise Crispell • Apr 2, 2015 at 7:45 am

Good Morning, I am Hayden Walks daughter Denise. I would like to say thank you for a most moving article. What a tribute to our father. Most people do not know the conditions that these men had to endure. Thank you again. Denise Crispell