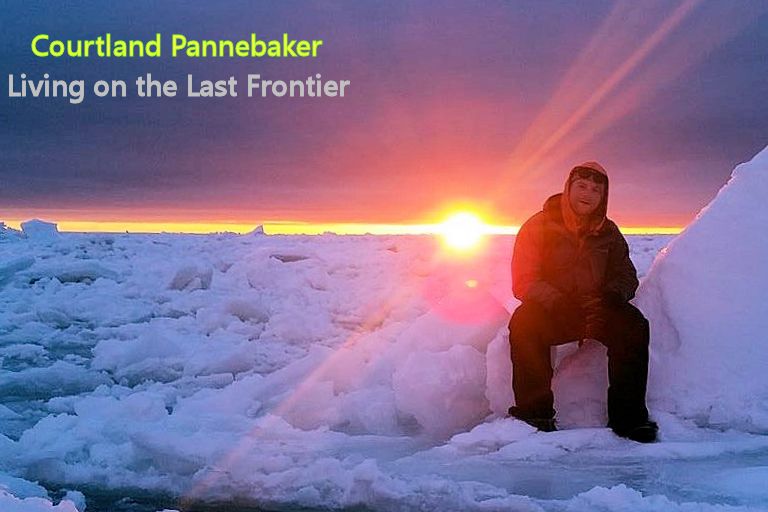

Alumni Spotlight: Winter on the Last Frontier

In November, the Eagle Eye wrote about TAHS graduate Courtland Pannebaker teaching in Gambell, Alaska. This is a follow-up on his year on St. Lawrence Island.

When he signed up for a year of teaching on one of the most remote islands in the Bering Sea, Tyrone grad Courtland Pannebaker knew it would be the adventure of a lifetime. His year has not disappointed, especially on a recent morning when he got to help with one of the most important and sacred traditions of Yupik culture: a whale hunt.

“To catch a whale, you must have a good striker at the front of the boat and a good boat captain driving to get you close enough to the whale. It also takes a bit of luck to spot a whale in the first place. There is a common Yupik idea that a whale actually gives itself to the worthy hunter,” said Pannebaker.

Pannebaker was not personally allowed to help catch the whale because of laws protecting bowhead whales. Only registered native whaling captains and crews are allowed to hunt whales. These captains (from eleven whaling communities) agree to the Cooperative Agreement between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission. They have specific rules that they have to follow, such as reporting all whales that they catch. According to the agreement above, whalers are only allowed to catch so many whales per year in order to protect endangered whale species.

To catch a whale, you must have a good striker at the front of the boat and a good boat captain driving to get you close enough to the whale. It also takes a bit of luck to spot a whale in the first place. There is a common Yupik idea that a whale actually gives itself to the worthy hunter.

— Pannebaker

While Pannebaker was not able to participate in the actual whale hunt, he was able to help bring the whale to shore and help butcher it.

“I stayed up to 5 am helping butcher a whale because I wanted to learn about it. My adrenaline was pumping all night. I had never experienced something so cool in my life. It was a 42 foot bowhead whale, and it took the whole village to pull and cut the meat and Mungtuk,” said Pannebaker.

After the whale was butchered, Pannebaker was excited to have a taste.

“It was very different at first because it was so exotic, but I grew to really enjoy the taste…I have a hard time describing whale, but I will say it is fantastic! I am so fortunate to have great cooks of any type of Yupik food. As for the whale, it is very hard to describe the texture. It also depends on how it is prepared. Is it aged? Is it baked? Are you having Mungtuk (blubber/skin) or the meat? Usually when the whale is not eaten raw, it is mixed with other ingredients to add flavor,” said Pannebaker.

However, this is not the only new adventure Pannebaker has experienced. Pannebaker has also had the opportunity to learn how to speak Yupik.

“I have learned many words, but the spelling is still something I am learning. I know many of the common animal names, as well as the colors, months, numbers, and other things that we teach the kids. I learn with the students during our Yupik time we have daily,” said Pannebaker.

Despite these amazing experiences, there were also some challenges to living in Gambell. One of the challenges that Pannebaker faced was the weather.

“The winter was brutal. The wind was like nothing I have ever experienced. It was piercing cold, but I survived and live to tell about it. As difficult as it was for me, this winter in Gambell was actually milder than normal. The sea ice melted faster again this year and made crabbing very difficult,” said Pannebaker.

There is also a limited amount of light available during the winter. However, Pannebaker didn’t find this to be a major obstacle.

“It didn’t get as dark as I expected. It wasn’t bad. It would get light around lunch time and get dark around 8 pm,” said Pannebaker.

Fortunately, Pannebaker was able to adjust to the lack of sunlight fairly easily. Many people who live so far north experience Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD), a type of depression that generally occurs during one season but then disappears during another. This most commonly occurs during the winter in places that receive little-to-no sunlight. Most people begin to have symptoms in September or October until April or May. These symptoms often include sleeping but still feeling tired, having trouble concentrating, losing interest in usual hobbies, and feeling sad or moody.

I overcame the extreme cold, a change in principals mid-year, having limited supplies, tremendous price increases on everyday items, and being cut off from mainland Alaska. But for the most part the challenges are easy to overcome because the rewards are endless!

— Pannebaker

Pannebaker said that he didn’t have any students who experienced SAD. However, he often had to create unique lesson plans in order to engage his students.

“I am flexible, I make things work with what I have…I like to use the subsistence and cultural influence when I teach. I like to use examples that the students have experienced to make it more relevant to them. My students here love basketball and hunting, so I use those references often when I teach,” said Pannebaker.

Living on the Last Frontier comes with many extremes. There are extreme hardships, but also extreme opportunities. Courtland has had the chance to experience them all.

“I overcame the extreme cold, a change in principals mid-year, having limited supplies, tremendous price increases on everyday items, and being cut off from mainland Alaska. But for the most part the challenges are easy to overcome because the rewards are endless!” said Pannebaker.

For those interested in learning more about whaling, check out the following stories:

“Remote Savoonga lands 4 whales as Arctic Alaska hunts get going” from the Alaska Dispatch News.

“Eskimo whalers seek ATF support to build a more humane bowhead bomb” from the Alaska Dispatch News.

“Climate Changes Lives of Whalers in Alaska” from NPR News.

Reading and writing are a big part of the reason senior Taylor Hoover decided to join the Eagle Eye staff team for the first time. She is ready to tackle...